Breaking barriers: How an Uzbek designer found his place in Europe's creative industry

Sherzod Mirzaakhmedov is an Uzbek designer who has been working at Media Monks in the Netherlands since 2019. “I was given tasks in design that I had never tried before, but that helped me grow and step out of my comfort zone,” says our protagonist, who has worked on projects for Google, Meta, BMW, and other major companies.

Фото: Kun.uz

Sherzod, originally from Tashkent, is 35 years old. Although he studied economics at university, he admits that his career has nothing to do with the field.

He spoke with Kun.uz about his journey to Europe for work, the environment and mentality there, and how he overcame the psychological barriers related to English.

From Tashkent to Europe: “First, you work for your portfolio, then your portfolio works for you”

My career can be divided into two parts. In Uzbekistan, I worked mostly with Russian-speaking clients as a freelancer. Now, I work entirely in English with European and American clients.

At the time, platforms for showcasing portfolios were scarce. One of the few specialized design platforms was Revision, which has since shut down. I used to post my work there, gaining both clients and valuable feedback. There was also free-lance.ru, where I regularly uploaded my work.

The key to success was not just publishing completed projects but also coming up with personal projects and designing them. When you're just starting, orders are limited, so you can redesign popular websites like Facebook or Google and add them to your portfolio. At first, you work for your portfolio, and later, your portfolio works for you.

In Uzbekistan, local designers did not charge as much as their Russian counterparts, which meant more orders. However, in 2013, when Russia and Ukraine grew apart, sanctions hit Russia, and the ruble depreciated, my income dropped 2–2.5 times. Many clients wanted to continue paying in rubles, but for me, that meant significantly lower earnings, so I lost many of them.

I then joined a company in Tashkent, while simultaneously translating my portfolio into English and adapting it for the European market on Dribbble and Behance. Over time, I transitioned to working with European clients.

From 2007 to 2018, I worked at Amayasoft in Tashkent, followed by Style Mix, Sapphire, DA Brander, and even Click for a brief period. I was also freelancing on the side.

The job interview & visa struggles

After uploading my portfolio to Dribbble and Behance, I received offers from major companies in Norway and Sweden. One of them was Media Monks in the Netherlands — my dream company.

They were looking for a visual designer, not a UI/UX designer. I went through three interviews over a year, including one with a designer who had 18–19 years of experience. But when the discussion turned to salary and relocation, I found the offer insufficient and declined.

Later, after getting married, I decided to make a major life change and accepted an offer from Media Monks.

The visa process was a nightmare. Dealing with two bureaucracies at once was exhausting. I had to prepare, translate, and submit documents multiple times because errors kept coming up. The visa was issued in Moscow, but I initially couldn’t get it due to an apostille mistake. Eventually, I managed to obtain it.

Moving to the Netherlands: “We had to adapt to a whole new world”

In early 2019, my wife and I moved to Hilversum, Netherlands. The company covered visa expenses, flights, and the first month’s rent. To help us experience Dutch culture, they rented a historic wooden house for us. The rent was over €2,500 per month, half of which I had to cover after my first paycheck.

The house had a strange smell, and the wooden floors creaked, making it uncomfortable. But what surprised us most was how frugal the Dutch are.

We lived in half of the house, while the landlord occupied the other half. He would leave us notes saying, “It’s bright enough outside; you’re using too many lights—please turn them off.” He even limited the hot water to five minutes, after which only cold water would flow, forcing us to shower quickly.

The language, people, and culture were all new to us, and the adjustment was tough.

“In the Netherlands, work-life balance is excellent”

Now, we’ve fully adapted, and the initial culture shock has passed.

Our children speak three languages: at school, they use Dutch, with us, they speak Uzbek and English. Our five-year-old daughter picked up Dutch within a year and now even helps us understand things.

One of the best aspects of life here is the work-life balance. Meetings can be left without issue if you need to pick up your child or go to the doctor.

Regardless of your position, work rarely extends past 5 PM. Childcare and healthcare are free, and playgrounds are available every 5–10 minutes walking distance.

“Food is not a priority here”

Food is not a major concern for the Dutch. Unlike in Uzbekistan, where food is central to life, here it is viewed practically. People often eat just a slice of bread with a piece of sausage or even plain bread.

Initially, we spent a lot on food, but even then, Dutch people found it excessive.

Winters are harsh, with darkness setting in by 4 PM, while summers remain bright until 10 PM. The air is clean, and the country is extremely family-friendly.

Regardless of your background — whether you are poor, disabled, or even a pet owner — the state ensures a comfortable life for everyone. There are even parks designed specifically for dogs.

“They threw me into a boiling pot”

On my first day at work, I felt extremely uncomfortable. The office was open-space, and everyone chatted freely, as if they had known each other for years.

I had never spoken so much English in one day. Then, suddenly, a designer fell ill, and I was asked to take over his project immediately. I was thrown into a boiling pot.

I had to work with the New York office on a campaign where customers could get free products by visiting different bars. Somehow, I managed to complete the project.

Initially, I specialized in web and mobile app design, but they hired me as a visual designer, which turned out to be a broader role. I had to design VR experiences, branding, broadcasting graphics, and much more. It was overwhelming at first, but I gradually adjusted.

“In some ways, we are ahead of Europe in design trends”

Now, all designers worldwide work in Figma, but the CIS countries adopted it earlier. When I joined Media Monks, I was shocked to find that nobody there knew how to use Figma!

My mentor at the company told me, “What is this? We don’t use Figma — download Photoshop.” I thought it was a joke! Eventually, Google mandated a switch to Figma, and suddenly, everyone came to me for guidance.

This experience made me realize that in some areas, designers in Uzbekistan are ahead of Europe.

"I couldn't speak English well until I overcame my psychological barriers"

I used to have a mental block when it came to languages. In Uzbekistan, if you speak Russian incorrectly, people laugh at you, and it's considered normal. But here, no one laughs at you for not knowing something or for mispronouncing a word. At first, I didn't know this, and I was very anxious. The more you think you must speak well, the worse you end up speaking. My problem wasn’t my vocabulary or grammar — it was a psychological block. If I made a single mistake, I would get nervous and lose my train of thought.

I gradually changed, and my colleagues at work helped me. They supported me in different areas—whether in language, projects, or cultural adaptation. When I worked on a project with Spaniards and saw how they spoke English, I overcame my anxiety. They were speaking English, but it sounded as if they were speaking Spanish. I could barely understand them, yet no one told them they were speaking poorly. Instead, people asked clarifying questions and kept the conversation going.

I had a Brazilian colleague who once told me, “You are trying too hard to resemble Europeans, to fit into their lifestyle. Bring your own culture into the conversation. Talk about your country. That will enrich the team. Don’t try to be like them — just be yourself, and don’t be ashamed of anything. I’m actually curious about your people, your food, your weather — talk about that.” After that, my psychological barriers disappeared, and my English improved.

“They entrusted me with tasks I knew nothing about”

After I started working, I saw myself more as a product designer, a UI designer. I told them to assign me work that suited me because I wasn’t a visual designer. They just said, "Keep working, you’ll get better." So, I started watching video tutorials and learning. I figured out the proper dimensions for designing in Photoshop. Eventually, my portfolio expanded, I stepped out of my comfort zone, and I kept expanding it.

After COVID, a new department called "Virtual Events" was created. When global events shifted online, there was a high demand for online platforms. I moved to this department and further broadened my portfolio. The work mainly involved live streams — someone would speak, and I had to create animations for scene transitions and design lower-thirds displaying names and titles. I had absolutely no experience in this field. I was surprised — why were they giving me tasks I had never done before? But I managed, and it helped me grow professionally.

Now, I work in my own field, designing websites and mobile applications. I focus on UI and product design. To be honest, I miss the time I worked in visual design. Web design is more about systematic design, while visual design requires more creativity and the creation of new elements. Platform design is mostly system-oriented — you establish a direction at the beginning, and then all pages and components follow a structured approach. Because of this, it can be more monotonous.

A brief overview of my workday

If I wish, I can go to the office three days a week and work from home for two days. However, due to the distance of my home and the need to take my children to kindergarten, I usually go to the office only once a week. In the morning, I check project tracking systems, smart sheets, and Google Calendar, reviewing my scheduled calls. Every day, we spend 5–10 minutes discussing who is working on what and identifying any issues. Throughout the day, I document our progress and send updates via email.

“The most challenging task in my career…”

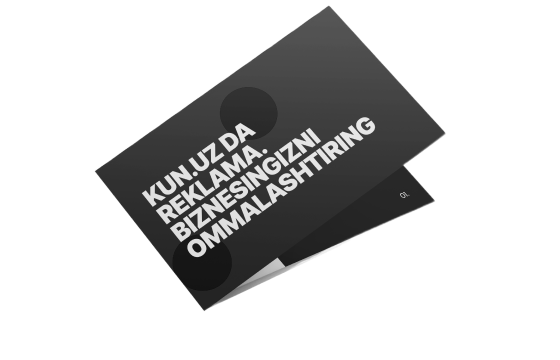

This happened at the beginning of my career. I was assigned a task related to a VR experience — putting on a headset would immerse you in a virtual world. A beautifully designed building had just been constructed in Amsterdam, and they wanted to sell it. With the VR headset, users could take a virtual tour inside the building. They would hold a controller in one hand to navigate the space, similar to moving around in Google Earth.

There were also "hotspots" — virtual portals that allowed users to teleport between different areas. For example, pressing a button at the lobby would instantly transport them to the apartments. Users could also open a virtual book containing interesting details. As they explored the apartments and found another hotspot, they would be taken to the office space.

My task was to design these portals in 3D, ensuring they provided a seamless transition with animation. Although I didn't create the animations, I had to prepare the storyboard for them, which was a major challenge. My mind operates in 2D, whereas this project required working in a 3D space.

At the same time, I was dealing with personal difficulties — my wife was pregnant, I had to handle legal paperwork, we needed to find a new place to live, my bank account wasn’t yet set up, and I hadn’t received my salary. On top of that, I was assigned this complex project. I requested to start with something easier and gradually take on harder tasks, but they told me to go ahead and complete it.

However, in situations like these, there is an important lesson: if you say, “I can't do it,” and they remove you from the project, you acknowledge that you’re not ready, which can psychologically set you back. Instead, they gave me a difficult challenge and said, "Push through — you can do it."

I barely managed to complete it by scouring Pinterest for references. In the end, the project manager treated us to Dutch snacks as a celebration. That was the moment I felt truly proud of myself.

The company works on orders from very large corporations. The downside is that so many people work on a single project that your individual contribution gets diluted. Since it's a team effort, it’s difficult to say, “This success is entirely because of my work.”

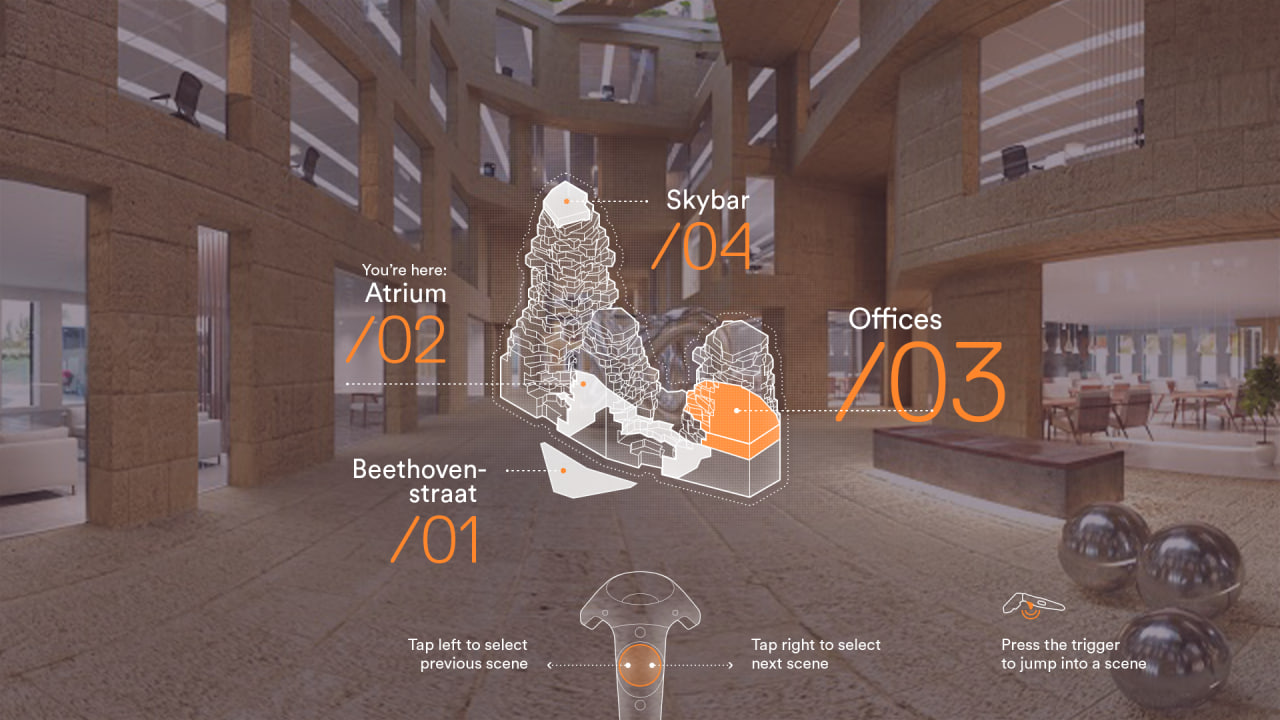

“Anna Frank’s virtual library was the best project I’ve worked on”

One of the projects I enjoyed the most was a mobile app about Anne Frank. In Amsterdam, there is a museum dedicated to Anne Frank’s house, and a project was launched to combat racism and xenophobia. She wrote her diary while hiding behind a bookshelf, and they created a virtual reality version of that very bookshelf. The project included Anne Frank’s room and various objects that, when interacted with, shared the experiences of people who had faced xenophobia or racism.

It was an incredibly interesting project that won major international awards. From a design perspective, it wasn’t particularly complex, but I consider it the best project I worked on at “Media Monks” because I truly loved its concept.

“I have worked with Google, Meta, Amazon, and BMW”

When I first joined the company, there was a designer named Antoine who exclusively worked on Google projects. I used to admire that and think, “Wow, he’s working on Google projects,” which felt like a huge deal to me. The first time I was assigned a Google project, I was nervous. But after completing it, I realized it wasn’t as difficult as I had imagined.

To be honest, I don’t particularly enjoy working with companies like Meta, Amazon, or BMW. Their large scale means their design systems are highly structured, leaving no room for creative freedom. You can’t step outside the system, and you can’t even make mistakes. However, making mistakes and learning from them is essential for growth. In these projects, there’s no room for trial and error. The entire system is interconnected — colors, fonts, and other elements are strictly systematized, making the work feel monotonous.

Additionally, there are always a hundred people overseeing everything and sharing their opinions. Because design is the first thing people see, everyone assumes they understand it and feel entitled to give feedback. When working for the U.S. market, for example, discussions often shift from design to text. I’ve witnessed situations where up to twenty copywriters were reviewing a single piece of text in a design. Since companies in the U.S. are highly cautious about wording — fearing potential lawsuits — more attention is paid to the text than the design itself.

What makes a good designer?

Over time, my perspective on what defines a good designer has evolved. Initially, I thought the best designer was someone skilled in Photoshop. Then, I believed it was someone who could create visually stunning designs. When I first joined this company, I considered design to be an art form.

I once read in Artemy Lebedev’s journal that “design is not art; it is functionality.” At the time, I was young and disagreed with him. “How can that be?” I thought. “Design is art; it comes from the heart.” But he was right — design is about function, solving business problems, and facilitating communication.

Yes, talent is important, but so is experience. Soft skills and secondary aspects like communication also play a crucial role. It’s not just about creating designs; you also need to be able to defend them. In Google projects, for instance, you often have to explain your design choices to 20–30 people. A good designer needs to work hard, read a lot, and integrate life experiences into their work.

How I overcame creative blocks

In the beginning, every designer experiences creative blocks. It’s nothing to be afraid of — it happens to everyone. You shouldn’t think, “I’ll never be a great designer because I can’t come up with good ideas.” Over my 18 years in the field, I’ve developed ways to automate certain processes.

Sometimes, the problem isn’t a lack of ideas but an excess of them, which can be just as challenging. You might wake up with a fresh perspective, notice mistakes, and start making changes. The next day, you see something else that needs fixing. This cycle can be counterproductive. Too many ideas can be overwhelming, so they need to be managed properly.

To overcome a creative block, I do something different — go for a walk, take a shower, read a book, or simply try not to think about the idea at all. If something isn’t working, forcing yourself won’t help. The best ideas often come naturally, and when they do, it’s a much more rewarding experience.

If you’re designing a digital product, such as a website, it’s not enough to just look at other websites for inspiration. Go outside, observe interesting architectural compositions, or appreciate the beauty of nature — these can spark fresh ideas. I once overcame a creative block while walking in nature, stepping on leaves, and distracting myself. The inspiration suddenly struck me, and I returned home to work on my project.

Books also provide a great source of inspiration. I find a lot of ideas in scientific fiction and magazines.

One key difference between designers here and those in Uzbekistan is that even the most experienced designers here start by compiling all previous works in a similar style (moodboard). They dedicate an entire workday to this process, and it’s not considered plagiarism — it’s about drawing inspiration. By the time the project is finished, the design looks completely different from the references. The moodboard serves as a creative push rather than a constraint.

Many types of designs have already been done before, so there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. The biggest cause of creative blocks is the pressure to create something groundbreaking. Thinking, “I must design something revolutionary,” can actually hinder creativity.

How does Uzbekistan’s design environment differ from here?

So far, doctors in the Netherlands have never prescribed gargling, injections, or medication. They simply tell you to get some fresh air, and it will pass. Even if you return in two weeks, they will just recommend taking paracetamol — nothing more. This is quite a conservative approach.

Now, from a design perspective, when I first arrived, Figma had just emerged and had not yet established itself in the market. At that time, Media Monks was still a local company, but it has since expanded significantly and become a global entity. It now has no choice but to adapt to new developments—artificial intelligence (AI) has already entered the scene. The prevailing belief is that whoever masters it the fastest will gain the greatest advantage. As a result, in the past few months, we have had numerous training sessions. Even now, every day, for about 15–20 minutes, we receive updates on AI-related innovations.

In Uzbekistan, certain lesser-known trends tend to gain traction more quickly. As I mentioned earlier, people are not afraid to take inspiration from others' work. For example, in Saudi Arabia, a new city called Qiddiya is being built, and we won the tender to design its website. A highly experienced creative designer developed the project’s design and presented it to us. The mood board was clearly visible—he had listed all the works that had inspired him, without trying to hide it. Especially when work needs to be completed quickly, drawing inspiration from others is entirely normal.

AI and design

My general perspective on artificial intelligence is this: When we were kids and computers were just emerging, our parents feared that computers would take over their jobs. Similarly, accountants once worried that automated calculation machines would make them obsolete. But in the end, computers turned out to be helpful tools — things that made our work easier rather than replacing us entirely. The typewriter, for example, didn’t eliminate jobs; it simply made writing more efficient.

The tasks that AI currently performs are also helpful to me. It cannot fully replace me yet because, throughout the course of a project, communication is key — when one person talks to another, critical decisions are made. AI can be a great assistant when starting a project, but the final product is still created by a human. The finishing touch is always made by a person. That’s why we should see AI not as a competitor but as an assistant.

Related News

13:02 / 29.01.2025

Meta leads the list of foreign taxpayers in Uzbekistan for 2024

12:27 / 07.12.2024

Uzbekistan’s ambassador presents credentials to King of the Netherlands

15:55 / 22.11.2024

Uzbekistan’s ambassador to Belgium extends role to the Netherlands

16:46 / 13.11.2024