Taliban’s Kushtepa canal: What are the implications for Uzbekistan?

The Amu Darya basin's surface water levels could decline by up to 18.9% by 2028 and 29.4% by 2030 due to the Kushtepa canal and climate change, exacerbating water scarcity and posing severe challenges for the region.

One of the most pressing and urgent issues on the agenda of Central Asian countries is water scarcity. Factors such as population growth, increased water consumption, climate change leading to extreme heat becoming the new norm, fewer snowy days, and the irrational use of water resources are exacerbating this problem.

Efforts are being made to mitigate the potential consequences of these factors as much as possible. However, in recent years, another serious challenge has emerged — the Kushtepa canal.

In March 2022, the Taliban government began constructing a massive canal in Balkh province, reviving a long-held ambition that had remained dormant for decades. The irrigation project, which is expected to be 285 km long, 100 meters wide, and 8.5 meters deep, could cost approximately $700 million.

The construction of the canal is planned to be carried out in three phases. As of late 2024, 81% of the second phase has been completed. The full completion of the canal is scheduled for 2028.

Key concerns

According to international experts, halting the construction at this stage is no longer feasible. A major concern is that if essential resources such as cement are used inadequately or if the project is poorly designed, the potential loss of water could increase significantly. Hundreds of thousands of cubic meters of water may seep into the ground, causing soil salinization. Given these risks, it is crucial to encourage the Taliban government to use modern technologies in the canal’s construction and to impose necessary technical requirements and obligations to minimize damage.

Due to recent global crises, such as the Russia-Ukraine war and conflicts in the Middle East, attention to Afghanistan's issues on the international stage has diminished. As a result, regional states must take the initiative in addressing this matter, especially considering doubts about the Taliban's ability to handle such complex engineering projects.

Additionally, there is no comprehensive agreement between Central Asian states and Afghanistan regarding the use and distribution of Amu Darya’s water. In 1946, the Soviet Union and the Afghan government held negotiations in Kabul, reaching an agreement, but the specific issue of water allocation was not directly addressed. Subsequent negotiations also failed to focus on this matter.

Currently, water relations in Central Asia are regulated by the 1992 Almaty Agreement, signed by Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The Interstate Coordinating Commission plays a key role in water resource management, developing and approving long-term water supply programs.

Additionally, water use in the region is also governed by the 1992 UN Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes. Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan have ratified this convention.

Afghanistan has not joined any of the aforementioned agreements on the use of Central Asia’s water resources. The most sensitive aspect of this issue is that while no one can deny Afghanistan’s right to use the Amu Darya, its absence from global and regional agreements means that the country has neither rights nor obligations regarding water use. This could lead to tensions in bilateral relations.

Impact of the Kushtepa canal on Uzbekistan

First, Uzbekistan is highly dependent on water supplies from neighboring countries, a fact frequently acknowledged by officials. About 85% of the country’s consumed water comes from external sources, and 90% of these water resources are used in agriculture.

According to some estimates, the overall reduction of surface water in the Amu Darya basin — taking into account the Kushtepa canal and climate change — could reach 18.9% by 2028 and 29.4% by 2030. Other studies suggest that within 5-6 years after the canal is completed and becomes operational, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan’s capacity to draw water from the Amu Darya may drop from 80% to 65%.

It is important to note that the Amu Darya is the primary water source for five regions of Uzbekistan: Surkhandarya, Kashkadarya, Bukhara, Khorezm, and Karakalpakstan.

Second, from an economic perspective, while agriculture’s share in Uzbekistan’s GDP has been declining—from 24.1% in 2020 to 19.2% in 2024 — any deterioration in this sector would have a significant impact on industries ranging from manufacturing to services. A decrease in crop yields could drive up prices of staple goods like rice and wheat, reducing household spending on secondary expenses such as foreign language courses for children, sports clubs, dining out, home or car purchases, and travel. Similarly, lower cotton yields would negatively affect textile exports.

Overall, in a country with a growing population, rising food prices can lead to reduced demand and consumption in other sectors of the economy. For example, by the end of 2023, Uzbekistan’s economic losses due to water shortages were estimated at $5 billion per year.

According to the World Bank, water scarcity could lead to a 30% decline in agricultural crop yields across Central Asia. In this regard, reducing reliance on water-intensive crops, such as ending cotton monoculture, has become one of the most pressing issues today.

Eldor Aripov, director of the Institute for Strategic and Regional Studies, also highlighted Central Asia’s vulnerability to climate change during the Munich Security Conference. He noted that over the past 30 years, temperatures in the region have risen by 1.5 degrees Celsius — twice as fast as the global average.

Third, the existing environmental situation could deteriorate further. Water shortages have already accelerated land degradation (affecting 37% of the region) and the rapid melting of glaciers (which have shrunk by 30% over the past 50-60 years). Dust and salt storms from the dried-up Aral Sea bed are harming both irrigated lands and public health, leading to drinking water shortages, the spread of dangerous diseases, and worsening living conditions. As a result, migration from affected areas is increasing year by year.

The construction of the Kushtepa canal and the subsequent reduction in Amu Darya’s water flow will further exacerbate these problems. In northern Afghanistan, where farmland will be developed, soil salinity must be regularly washed away. The only destination for this saline drainage water is the Amu Darya, which would worsen an already critical — sometimes catastrophic — environmental situation in the river’s middle and lower reaches. The combination of water scarcity and rising salinity will make farming in these areas even more challenging, meaning that the Kushtepa canal could contribute to increased soil salinization.

Changes in water volume may also require modifications or reconstruction of regional water infrastructure, adding further financial burdens.

In conclusion, rural populations, who are highly dependent on agriculture, have limited ability to adapt to new conditions and spend a large portion of their income on food, will be the hardest hit by water shortages. The ongoing depletion of available resources could further worsen the situation.

Recommended

List of streets and intersections being repaired in Tashkent published

SOCIETY | 19:12 / 16.05.2024

Uzbekistan's flag flies high on Oceania's tallest volcano

SOCIETY | 17:54 / 15.05.2024

New tariffs to be introduced in Tashkent public transport

SOCIETY | 14:55 / 05.05.2023

Onix and Tracker cars withdrawn from sale

BUSINESS | 10:20 / 05.05.2023

Latest news

-

Uzbekistan leads Central Asia in medal count at FISU World University Games in Germany

SOCIETY | 12:23

-

Tashkent Metro to suspend train service at six more stations for maintenance

SOCIETY | 12:07

-

High spending and shady contracts: Anti-Corruption Agency launches probe into Khanabad music festival

BUSINESS | 22:25 / 26.07.2025

-

Soaring gasoline prices and consumer rights issues spark debate in Uzbekistan

POLITICS | 19:50 / 26.07.2025

Related News

12:40 / 23.07.2025

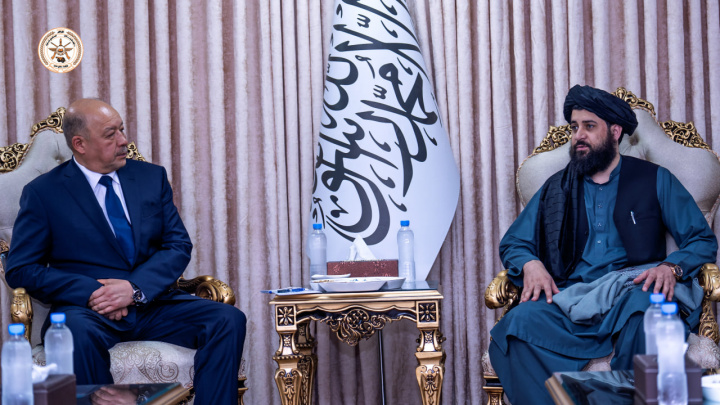

Uzbekistan’s State Security Service chief meets Taliban Defense Minister in Kabul

12:54 / 18.07.2025

Uzbekistan and Afghanistan strengthen dialogue on law enforcement and stability

12:04 / 18.07.2025

Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan agree to develop new railway corridor

11:49 / 04.07.2025