Subsidizing energy: Why is Uzbekistan keen on keeping the policy the richest countries could not afford?

In the 1930s, the deserts of Arabia along the coast of the Persian Gulf were populated with tribal people whose only source of wealth were camels and who got by in the harsh climatic conditions thanks to fishing or pearl diving. When oil and gas were discovered, life for these people started to change. A few decades later, in the 1970s, these Arab colonies gained independence from the British Empire and formed states that we all know today as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Oman and Qatar. These relatively small and sparsely populated rentier states now account for over 40% of the global proven crude oil reserves and 22.2% of the entire gas reserves of the world. Naturally, all of the money that the ruling families of these countries received from exporting oil and gas was eventually shared with the relatively small population of locals. Thus, the Gulf Arabs became one of the richest peoples in the world. For example, the GDP per capita in Qatar is $50,000 and $36,284 in the UAE, compared to $1,750 in Uzbekistan. In reality, citizens of these states are even much wealthier than represented by these figures, as the majority of the population are expatriate workers who have no share in the oil and gas export revenue of the governments.

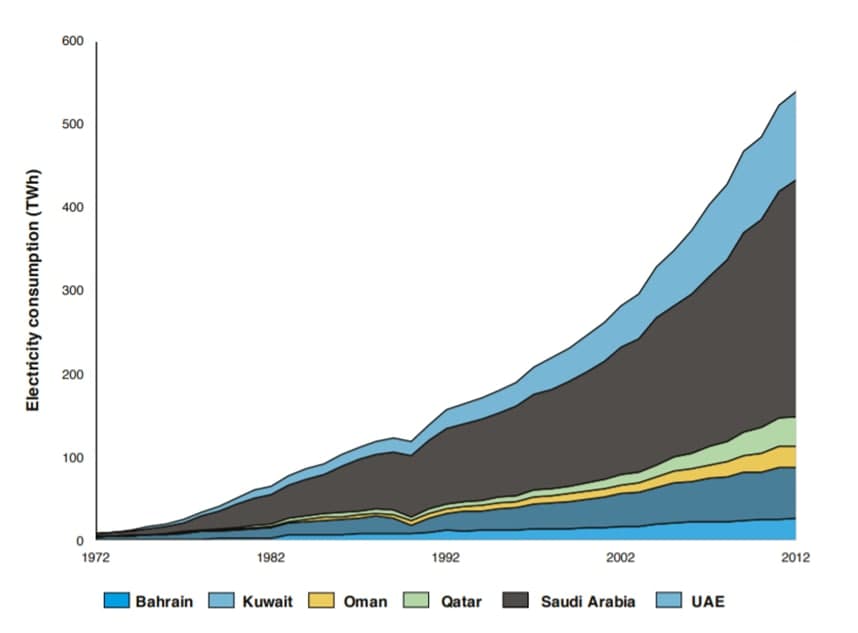

Jim Krane, the author of “Energy Kingdoms,” provides a detailed description of the radical changes in the lifestyles of the citizens that all this oil wealth caused in his book. In 1970, virtually no household had access to electricity, and hence refrigerator or air conditioner, which meant a miserable life under the year-long scorching Arabian sun. By 2010, however, energy consumption had reached such a level that in per capita terms, these countries consumed 10 times more energy than the global average. The locals bought extremely energy-inefficient cars, the most popular of which is Toyota Land Cruiser consuming around 16 litres of petrol per 100 km, and their governments installed air conditioning virtually everywhere, including streets and football stadiums. In the period from 1971 to 2015, the domestic oil demand rose by 521% in Kuwait, by 12,500% in Qatar, and by a whopping 27,733% in the UAE. All of this was due to the fact that the governments of these countries subsidized energy, creating a huge gap between the real price of oil and gas, dictated by the world markets and the price on the domestic market.

(Electricity consumption in the Arab Gulf in the period from 1972 to 2012)

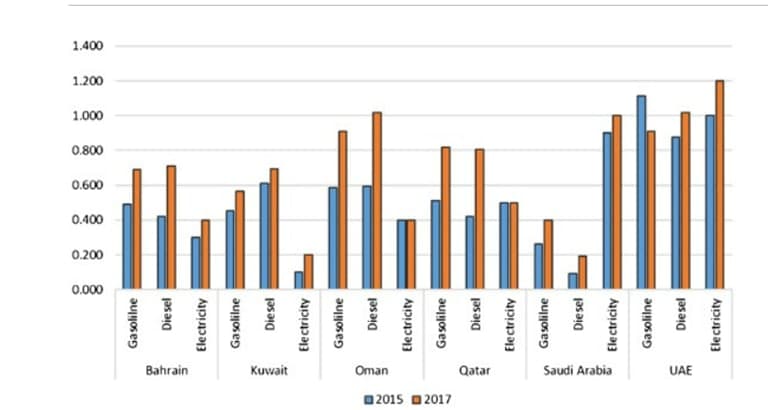

Eventually, these states started consuming more oil and gas than they were exporting, which meant massive losses for their economies that were almost entirely dependent on the export of these resources. The elites perceived energy subsidies as a central part of the “social contract” between them and the people. In exchange for the population’s political consent, the governments provided lavish energy subsidies. That, however, needed to stop, as if continued further, this unsustainable policy of energy subsidies jeopardized the economic stability of the states. In 2014, the price of oil fell by 50%, putting huge pressure on the budgets of the Arab Gulf states. The confluence of the economic pressure and the new coming rulers’ political will reformed the subsidization policy. Although not removed completely, the subsidies were largely reduced in the entire region. Over the three-year period from 2015 to 2018, gasoline prices rose by 41% in Kuwait, by 134% in Qatar, and by 51% in the UAE.

(Prices of energy sources and electricity in the Arab Gulf between 2015 and 2017)

The realization of the untenability of such an economic arrangement, experts argue, might as well have saved these countries from a fast-approaching economic collapse. The money that the governments saved by cutting the energy subsidies was rechanneled into the creation of more public jobs that were provided to citizens. Although not the wisest decision, as guaranteeing undemanding well-paying public jobs disincentivizes cultivation of skills among the local population, now these countries are undisputably better off than they were before.

You may wonder why this story is important. Uzbekistan, though 29 times poorer than Qatar, continues the policy that countries like Qatar deemed too expensive to sustain. In 2020, Uzbekistan imported natural gas worth $50,4 million and its exports of gas declined 4,7 times. In 2021, Uzbekistan officially became a net-importer of natural gas, increasing its purchase of the Turkmen gas from “Lukoil” from 0,9 billion cubic metres in the entire 2020 up to 1,5 billion cubic metres in just the first quarter of 2021. Despite the fact that we are buying resources instead of owning and exporting them, like the rich Arab states, we are still subsidizing the use of these expensive fossil fuels. While the size of subsidies has been on the decline since 2018 (which is partly explained by the global fall in the oil price during the pandemic), they still make up 6,6% of our GDP. To compare, our expenditure on education accounts for only 5,1% of GDP, while expenditure on healthcare constitutes 5,3%, according to the latest data from World Bank.

Now, before you call me crazy for speaking against subsidies that ostensibly help the poor to gain access to gas and electricity, let me explain why this policy actually hurts the less prosperous citizens of our country.

Uzbekistan has one of the cheapest electricity in the world. And while this may seem like a good thing, the way we obtain such a low price makes our economy especially precarious in the long-run. To put this into perspective, along with us at the top of the list of countries with the cheapest electricity are Libya, Angola, Sudan, and other incredibly poor nations. The irony of the cheap electricity is in that it is favored by poorer countries who fail to cover all of their population with energy, not despite but precisely because of their energy subsidies. The lower the government tries to push the price of energy, the fewer households it can provide with this artificially cheap electricity. Subsidies cause, not ameliorate the existing gaps in infrastructure. If the provision of energy was privatized, or at least not subsidized as heavily, there would be incentives to expand the infrastructure, thereby connecting more households to the grid.

Energy subsidies are bad for yet another reason: they perpetuate economic inequality. A person who owns a car receives a larger share of subsidies, because he buys petrol at a cheaper price, while someone who does not have a car cannot benefit from this policy. To simplify, if your neighbor owns Lexus, and you drive Chevrolet Matiz, then obviously you consume much less of the subsidized petrol than your richer neighbor. Let’s say the government’s subsidies reduce the real price of petrol by half, and you spend $100 on fuel per month, then it would mean that you are benefitting $100 from the energy subsidies. Your neighbor, say, spends $500 on petrol a month, meaning that the size of his benefit from the subsidies is also $500. At the end of the day, then, your neighbor receives $400 more from the government than you do, and all of it is paid for by taxpayers. Similarly, a household that spends more energy because they have a TV, vacuum cleaner and a coffee maker receive much more in subsidy benefits than a family who cannot afford to own such home appliances. In other words, energy subsidies create an economic structure that takes away from the poor in the form of taxes and reallocates those funds to the rich. According to the International Monetary Fund, in Egypt, the poorest 40% of the population received only 3% of subsidies on gasoline and 7% of subsidies on natural gas.

Uzbekistan reduced its average import tariffs from 14.9% in 2017 to 5,6% in 2019, which is unequivocally good. Ironically, however, Uzbekistan still imposes exuberant import tariffs on automobile cars, which is equivalent to taxing car owners, but subsidizes energy, like natural gas, which is the same as incentivizing car owners. The two contradictory policies offset one another, yet the country’s budget loses a lot. Instead of practicing such distortive trade policies, our country should embrace free trade if we want to keep robust economic growth. Both tariffs and subsidies serve as obstacles on our path.

Merely rolling back the subsidies, however, will be equivalent to penalizing the consumers of energy for the years of accumulated government inefficiencies. The sector needs greater privatization efforts to mitigate the price effects of the abolishment of subsidies. The government of Uzbekistan is interested in privatizing the generation of energy, as evidenced by the recent comments by Minister of Finance Timur Ishmetov. Although competition between profit-seeking companies in generation will certainly help push the final price of electricity down, it is important to draw the line between generating companies and retailers. If the producers are prohibited from selling energy directly to the final users, it will be harder for them to simply transfer their otherwise optimizable costs to the consumers.

Apart from generation and sale, the electricity also needs to be distributed. Both transmission (high-voltage, commercial lines) and distribution (low-voltage, local lines) of electricity are considered areas of natural monopolies for their high fixed costs. Moreover, once your household is connected to the power grid, it is virtually impossible to change the distributor, which will mean the impossibility of a competition-based downward pressure on prices. Therefore, although the state ownership is inevitable, public-private partnerships in this regard may help optimize the management of distribution. Needless to say, the allocation of public-private partnership contracts and privatization of the existing energy-generating facilities should be done exclusively through transparent and proven methods, like auctions.

The reform of energy subsidies, although a challenging process, should continue the government’s decisive market-oriented liberal reforms to put Uzbekistan on the path towards sustainable economic growth. The money spent on energy subsidies will find a much better use if invested in education or split evenly among the population, which would help prevent the rapid aggravation of economic inequality.

Recommended

List of streets and intersections being repaired in Tashkent published

SOCIETY | 19:12 / 16.05.2024

Uzbekistan's flag flies high on Oceania's tallest volcano

SOCIETY | 17:54 / 15.05.2024

New tariffs to be introduced in Tashkent public transport

SOCIETY | 14:55 / 05.05.2023

Onix and Tracker cars withdrawn from sale

BUSINESS | 10:20 / 05.05.2023

Latest news

-

Uzbekistan tops medal table at Asian Cadet Judo Cup in Kazakhstan

SPORT | 18:42 / 05.07.2025

-

Uncertainty grows as new homes remain without gas supply

SOCIETY | 17:46 / 05.07.2025

-

Uzbekistan plans to launch national ferry service in Caspian Sea

SOCIETY | 16:03 / 05.07.2025

-

Dozens of violations, zero accountability: Fergana police cancel fines for chief’s wife’s car

SOCIETY | 16:02 / 05.07.2025

Related News

14:46 / 05.07.2025

“Preparing for winter” — the never-ending excuse for power outages in Tashkent

21:21 / 04.07.2025

New wind power plant to be built in Tashkent region

12:26 / 03.07.2025

Over 135 billion UZS worth of electricity and gas stolen in June

19:10 / 02.07.2025